SANDY BROWN is pleased to present "Apotheke" by Hannah Rose Stewart. This is the artist’s first solo exhibition at the gallery.

—

Telegram Industrial Complex

Before information flew across the internet, mental diseases spread through cities like viruses, spawning new psychopathies as a response to the urban horror. Of all the earliest accounts, the one that stands out is ‘neurasthenia’, a phrase coined by American neurologist George Miller Beard in 1980 to refer to the ‘nervous exhaustion’ born out of spatial fear in cities, its symptoms including general malaise, hysteria, insomnia and hypochondriasis. In his 1907 book Abstraction and Empathy, the art historian Wilhelm Worringer used another term, the “spiritual dread of space”, which describes the desire for abstraction when faced with inner unrest brought about by hostile surroundings. According to Worringer, the subject responds to these psychological disturbances by retreating into themselves – or, withdrawing from reality by creating their own.

Today, we have entered an era of technological acceleration that evokes a similar kind of spiritual alienation, where the intensity and precariousness of late capitalism creates an atmosphere where we are both overstimulated and disassociated. Transfixed in the eternal scroll, our anxious, pattern-seeking brains can no longer retreat ‘indoors’ because the outside world lurks within our screens. Our personal lives are spread across social media, our information stored in the Cloud, our online behaviour logged and fed back to us through targeted ads. Networked communication allows us to connect to each other more than ever, and yet violent images flood our feeds exposing us to man made horrors beyond our comprehension.

Scrolling the feed is a disorientating and sometimes violent experience. Nowhere else will you encounter cat memes and thirst traps followed by clips of dying children within a matter of seconds. Or have your reality put into question over a single AI-generated image. Nowadays it’s easier to assume that nothing you see online is ‘real’ because anything we see has been processed through various kinds of apps, filters and prompts that distort the material world in favour of the fantastical and uncanny. On the contrary, we might draw the conclusion that everything we see online is real because we choose it to be. Most of our beliefs are funnelled through filter bubbles and unverified news sources, which creates a particular strain of madness. Just as the early city dweller might feel isolated yet overwhelmed in the overcrowded streets, the post-digital subject is showing similar symptoms of spatial fear, which manifest both on and off-screen.

In the 19th century, opium dens served as spaces where people could retreat from the debilitating atmosphere of big cities. A century on, drugs, specifically ecstasy, were central to the collective release of the 90s dancefloor, flooding the audience’s brains with artificially simulated feelings – from the heady euphoric highs to the soul-crushing lows of the comedown. While we still go to the dancefloor in search of connection, ‘E-emotionality’ – once a core tenet of clubbing – has been replaced with more asocial chemicals such as ketamine or designer drugs like 3mmc. Perhaps the shift mirrors our dwindling excitement, the turn-of-the-century optimism replaced with a cultural paralysis, the overload of visual and audio stimuli creating a short circuit in our brains where we have more access to information than ever before, which paradoxically makes us less able to actually absorbing that very information.

The perpetual connectivity of being terminally online, without the actual connection that comes from IRL interactions is also perhaps what motivates the desire to switch off our brains, like one would previously ‘switch off’ their electronic devices. The irony is that dissociating through chemicals mirrors exactly the conditions we feel online – retreating deeper in our own little worlds, or personal mythologies, while simulating the conditions of connectivity through the dimming down of our social inhibitions. Even the ways these drugs are distributed, through encrypted chats on secret Telegram channels (as opposed to face-to-face), is another way in which networked communication plays into these parasocial patterns – the networked nature of communication reconfiguring our club rituals is what I refer to as the Telegram Industrial Complex.

Taking stimulants makes you more robotic, less human. It becomes easier to lock in – both to the hyper-synthetic cycles of production and to the conveyor belt of DMs, memes, tweets, images and short-form videos that pop up erratically on our screens and splicing our attention across a never ending stream of digital channels. For Mark Fisher, ADHD was “a pathology of late capitalism – a consequence of being wired into the entertainment control circuits of hypermediated consumer culture”. An answer to our ever-dwindling attention spans then, ADHD-friendly stimulants help us to avoid burnout endemic to late capitalism through the hyper-mobilising of our sensory facilities (a similar story is behind coffee production and early capitalism). Just as a chameleon might change colour to adapt to their surroundings, the disembodied subject disassembles themselves into smooth and machinic parts, rearranging their mental facilities to fit into their chaotic environment, the cathartic reaction of which is felt most viscerally on the dancefloor.

When an individual becomes too absorbed in the external spaces surrounding them, the spiritual dread becomes inevitable. While this transformation might be useful in some ways, the malfunctioning subject is forgiven for wanting to abstract themselves completely, to find ways to exist beyond spatial systems and therefore freedom – from capital, censorship, identity. Through screens we select our realities, moving between barriers that transcend virtual landscapes, rewiring our neurological circuits to better understand ourselves and the noise surrounding us.

— Text by Günseli Yalcinkaya

Special thanks to Leona Tiemessen, Elza Ozolite, Robert Vimmermoth, Tebs Lethapa, Finley Stewart, Matt Dell, Günseli Yalcinkaya, Norbert Kühn

Hannah Rose Stewart

'Headbanger', 2024

Stainless steel, aluminium profiles, painted MDF board, inkjet print, lamb skin, foam, salt, boot polish, pink bandage with wadding

120 × 138 cm

Unique

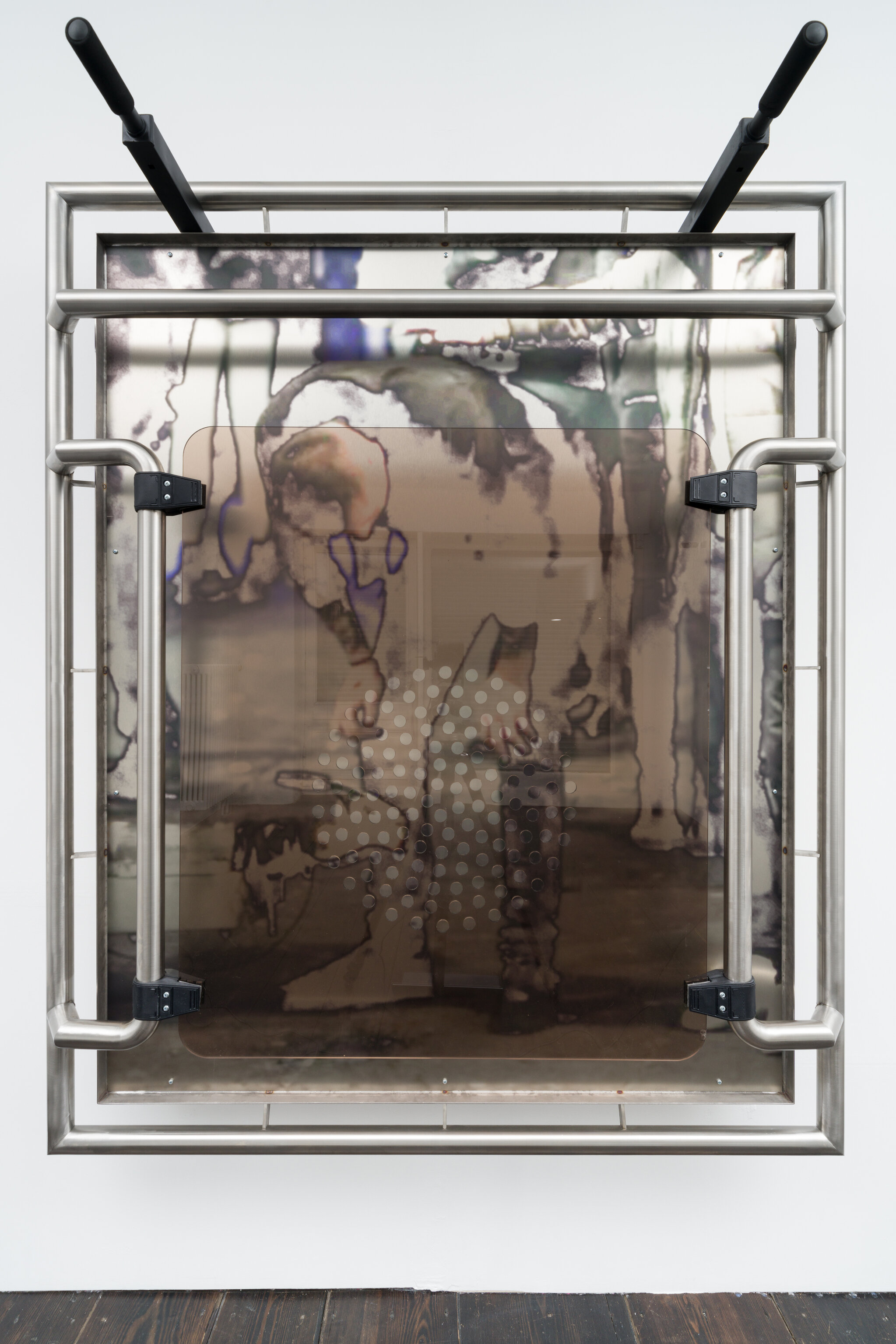

Hannah Rose Stewart

'Meadow Well', 2024

Stainless steel, aluminium profiles, UV print on aluminium, Perspex, 3D printed polyurethane resin

168 × 138 cm

Unique

Hannah Rose Stewart

'Sinners 2', 2024

Stainless steel, aluminium profiles, Perspex, painted MDF board, lamb skin, foam, metal clamps, nylon straps

168 × 138 cm

Unique